Historical Jesus

| Part of a series on |

|

The term "historical Jesus" refers to the life and teachings of Jesus as interpreted through critical historical methods, in contrast to what are traditionally religious interpretations.[1][2] It also considers the historical and cultural contexts in which Jesus lived.[3][4][5][6] Virtually all scholars of antiquity accept that Jesus was a historical figure, and the idea that Jesus was a mythical figure has been consistently rejected by the scholarly consensus as a fringe theory.[7][8][9][10][11] Scholars differ about the beliefs and teachings of Jesus as well as the accuracy of the biblical accounts, with only two events being supported by nearly universal scholarly consensus: Jesus was baptized and Jesus was crucified.[12][13][14][15]

Reconstructions of the historical Jesus are based on the Pauline epistles and the gospels, while several non-biblical sources also support his historical existence.[16][17][18] Since the 18th century, three separate scholarly quests for the historical Jesus have taken place, each with distinct characteristics and developing new and different research criteria.[19][20] Historical Jesus scholars typically contend that he was a Galilean Jew and living in a time of messianic and apocalyptic expectations.[21] Some scholars credit the apocalyptic declarations of the gospels to him, while others portray his "Kingdom of God" as a moral one, and not apocalyptic in nature.[22]

The portraits of Jesus that have been constructed through history using these processes have often differed from each other, and from the image portrayed in the gospel accounts.[23] Such portraits include that of Jesus as an apocalyptic prophet, charismatic healer, Cynic philosopher, Jewish messiah, prophet of social change,[24][25][6] and rabbi.[26][27] There is little scholarly agreement on a single portrait, nor the methods needed to construct it,[23][28][29][3] but there are overlapping attributes among the various portraits, and scholars who differ on some attributes may agree on others.[24][25][30]

Historical existence

[edit]Virtually all scholars of antiquity agree that Jesus existed.[8][9][31] Historian Michael Grant asserts that if conventional standards of historical criticism are applied to the New Testament, "we can no more reject Jesus' existence than we can reject the existence of a mass of pagan personages whose reality as historical figures is never questioned."[32] There is no indication that writers in antiquity who opposed Christianity questioned the existence of Jesus.[33][34]

Since the 1970s, various scholars such as Joachim Jeremias, E. P. Sanders and Gerd Theissen have traced elements of Christianity to currents in first-century Judaism and have discarded nineteenth-century minority views that Jesus was based on previous pagan deities.[35] Mentions of Jesus in extra-biblical texts exist and are supported as genuine by the majority of historians.[8] Differences between the content of the Jewish Messianic prophecies and the life of Jesus undermine the idea that Jesus was invented as a Jewish Midrash or Peshar.[36]: 344–351 The presence of details of Jesus' life in Paul, and the differences between letters and Gospels, are sufficient for most scholars to dismiss mythicist claims concerning Paul.[36]: 208–233 [37] Theissen says "there is broad scholarly consensus that we can best find access to the historical Jesus through the Synoptic tradition."[38] Bart D. Ehrman adds: "To dismiss the Gospels from the historical record is neither fair nor scholarly."[8]: 73 One book argues that if Jesus did not exist, "the origin of the faith of the early Christians remains a perplexing mystery."[36]: 233 Eddy and Boyd say the best history can assert is probability, yet the probability of Jesus having existed is so high, Ehrman says "virtually all historians and scholars have concluded Jesus did exist as a historical figure."[39]: 12, 21 [40] Historian James Dunn writes: "Today nearly all historians, whether Christians or not, accept that Jesus existed".[41] In a 2011 review of the state of modern scholarship, Ehrman wrote: "He certainly existed, as virtually every competent scholar of antiquity, Christian or non-Christian, agrees."[42]: 15–22

The Christ myth theory is the proposition that Jesus of Nazareth never existed, or if he did, he had virtually nothing to do with the founding of Christianity and the accounts in the gospels.[43] In the 21st century, there have been a number of books and documentaries on this subject. For example, Earl Doherty has written that Jesus may have been a real person, but that the biblical accounts of him are almost entirely fictional.[39]: 12 [44][45][46] Many proponents use a three-fold argument first developed in the 19th century: that the New Testament has no historical value with respect to Jesus's existence, that there are no non-Christian references to Jesus from the first century, and that Christianity had pagan and/or mythical roots.[47][48]

Contemporary scholars of antiquity agree that Jesus existed, and biblical scholars and classical historians view the theories of his nonexistence as effectively refuted.[8][10][49][50][51] Robert M. Price, an atheist who denies the existence of Jesus, agrees that his perspective runs against the views of the majority of scholars.[52] Michael Grant (a classicist and historian) states that "In recent years, no serious scholar has ventured to postulate the non-historicity of Jesus, or at any rate very few have, and they have not succeeded in disposing of the much stronger, indeed very abundant, evidence to the contrary."[10] Richard A. Burridge states, "There are those who argue that Jesus is a figment of the Church's imagination, that there never was a Jesus at all. I have to say that I do not know any respectable critical scholar who says that anymore."[49][36]: 24–26

Sources

[edit]

The New Testament represents sources that have become canonical for Christianity, and there are many apocryphal texts that are examples of the wide variety of writings in the first centuries AD that are related to Jesus.[53]

Non-Christian sources that are used to study and establish the historicity of Jesus include Jewish sources such as Josephus, and Roman sources such as Tacitus.[17][18]

New Testament sources

[edit]Pauline epistles

[edit]The Pauline epistles are dated to between AD 50 and 60 (i.e., approximately twenty to thirty years after the generally accepted time period for the death of Jesus), and are the earliest surviving Christian texts that include information about Jesus.[54]

Although Paul the Apostle provides little biographical information about Jesus[55] compared to the Gospels, he was a contemporary of Jesus and does make it clear that he considers Jesus to have been a real person[note 1] and a Jew.[56][57][58][59][note 2] Moreover, he claims to have met with James, the brother of Jesus.[60][note 3] Paul states that he personally knew and interacted with eyewitnesses of Jesus such as his most intimate disciples (Peter and John) and family members (his brother James) starting around 35 or 36 AD, within just a few years after the crucifixion, and got some direct information about his life from them.[62][63][64] From Paul's writings alone, a fairly full outline of the life of Jesus can be found: his descent from Abraham and David, his upbringing in the Jewish Law, gathering together disciples, including Cephas (Peter) and John, having a brother named James, living an exemplary life, the Last Supper and betrayal, numerous details surrounding his death and resurrection (e.g. crucifixion, Jewish involvement in putting him to death, burial, resurrection, seen by Peter, James, the twelve and others) along with numerous quotations referring to notable teachings and events found in the Gospels.[65][36]: 209–228

Synoptic Gospels

[edit]

The Synoptic Gospels are the primary sources of historical information about Jesus and of the religious movement he founded.[21][66][67][note 4] These religious gospels – the Gospel of Matthew, the Gospel of Mark, and the Gospel of Luke – recount the life, ministry, crucifixion and resurrection of a Jew named Jesus who spoke Aramaic and wore tzitzit.[68][69] There are different hypotheses regarding the origin of the texts because the gospels of the New Testament were written in Greek for Greek-speaking communities,[70] and were later translated into Syriac, Latin, and Coptic.[71]

The fourth gospel, the Gospel of John, differs greatly from the Synoptic Gospels and scholars generally consider it to be less useful for reconstructions of the life of Jesus than the Synoptic Gospels. As James Crossley and Robert J. Myles explain, John "is of limited use for reconstructing the life of the historical Jesus."[72] However, since the third quest, John's gospel is seen as having more reliability than previously thought or is sometimes seen as even more reliable than the synoptics.[73][74] For example, certain sayings in John are as old as or older than their synoptic counterparts, his representation of the topography around Jerusalem is often superior to that of the synoptics, his testimony that Jesus was executed before, rather than on, Passover, might well be more accurate, and his presentation of Jesus in the garden and the prior meeting held by the Jewish authorities are more historically plausible than their synoptic parallels.[75]

Historians often study the historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles when studying the reliability of the gospels, as the Book of Acts was seemingly written by the same author as the Gospel of Luke.[76]

Non-biblical sources

[edit]In addition to biblical sources, there are a number of mentions of Jesus in non-Christian sources.[77][16]

Thallos

[edit]Biblical scholar Frederick Fyvie Bruce says the earliest mention of Jesus outside the New Testament occurs c. 55 AD from a historian named Thallos. Thallos' history, like the vast majority of ancient literature, has been lost but not before it was quoted by Sextus Julius Africanus (c. 160 – c. 240 AD), a Christian writer, in his History of the World (c. 220). This book likewise was lost, but not before one of its citations of Thallos was taken up by the Byzantine historian George Syncellus in his Chronicle (c. 800). There is no means by which certainty can be established concerning this or any of the other lost references, partial references, and questionable references that mention some aspect of Jesus' life or death, but in evaluating evidence, it is appropriate to note they exist.[78]: 29–33 [79]: 20–23

Josephus and Tacitus

[edit]There are two passages in the writings of the Jewish historian Josephus, and one from the Roman historian Tacitus, that are generally considered good evidence.[77][79]

Josephus' Antiquities of the Jews, written around AD 93–94, includes two references to the biblical Jesus in Books 18 and 20. The general scholarly view is that while the longer passage, known as the Testimonium Flavianum, is most likely not authentic in its entirety, it is broadly agreed upon that it originally consisted of an authentic nucleus, which was then subject to Christian interpolation.[80][81] Of the other mention in Josephus, Josephus scholar Louis H. Feldman has stated that "few have doubted the genuineness" of Josephus' reference to Jesus in Antiquities 20, 9, 1 ("the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James"). Paul references meeting and interacting with James, Jesus' brother, and since this agreement between the different sources supports Josephus' statement, the statement is only disputed by a small number of scholars.[82][83][84][85]

Roman historian Tacitus referred to "Christus" and his execution by Pontius Pilate in his Annals (written c. AD 116), book 15, chapter 44.[86] Robert E. Van Voorst states that the very negative tone of Tacitus' comments on Christians makes the passage extremely unlikely to have been forged by a Christian scribe[79] and the Tacitus reference is now widely accepted as an independent confirmation of Jesus's crucifixion.[87][88]

Talmud

[edit]Other considerations outside Christendom include the possible mentions of Jesus in the Talmud. The Talmud speaks in some detail of the conduct of criminal cases of Israel whose texts were gathered together from 200 to 500 CE. Johann Maier and Bart D. Ehrman argue this material is too late to be of much use. Ehrman explains that "Jesus is never mentioned in the oldest part of the Talmud, the Mishnah, but appears only in the later commentaries of the Gemara."[89][42]: 67–69 Jesus is not mentioned by name, but there is a subtle attack on the virgin birth that refers to the illegitimate son of a Roman soldier Pantera (Ehrman says, "In Greek the word for virgin is parthenos"), and a reference to Jesus' miracles as "black magic" learned when he lived in Egypt (as a toddler). Ehrman writes that few contemporary scholars treat this as historical.[42]: 67 [90]

Mara bar Serapion

[edit]There is only one classical writer who refers positively to Jesus and that is Mara bar Serapion, a Syriac Stoic, who wrote a letter to his son, who was also named Serapion, from a Roman prison. He speaks of the execution of 'the wise king of the Jews' and compares his death to that of Socrates at the hands of the Athenians. He links the death of the 'wise king' to the Jews being driven from their kingdom. He also states that the 'wise king' lives on because of the "new laws he laid down". The dating of the letter is disputed but was probably soon after 73 AD.[91]

Scholars such as Robert Van Voorst see little doubt that the reference to the execution of the "king of the Jews" is about the death of Jesus.[92] Others such as Craig A. Evans see less value in the letter, given its uncertain date, and the ambiguity in the reference.[93]

Critical-historical research

[edit]Historical criticism, also known as the historical-critical method or higher criticism, is a branch of criticism that investigates the origins of ancient texts in order to understand "the world behind the text".[94] The primary goal of historical criticism is to discover the text's primitive or original meaning in its original historical context and its literal sense. Historical criticism began in the 17th century and gained popular recognition in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Historical reliability of the Gospels

[edit]The historical reliability of the gospels refers to the reliability and historic character of the four New Testament gospels as historical documents. Historical reliability is not dependent on a source being inerrant or void of agendas since there are sources that are considered generally reliable despite having such traits (e.g. Josephus).[95] The question of reliability is a matter of ongoing debate.[96][97][98][99][100][101][excessive citations]

Historians subject the gospels to critical analysis by differentiating authentic, reliable information from possible inventions, exaggerations, and alterations.[21] Since there are more textual variants (200,000–400,000) than words in the New Testament,[102] scholars use textual criticism to determine which gospel variants could theoretically be taken as original. To answer this question, scholars have to ask who wrote the gospels, when they wrote them, what was their objective in writing them,[103] what sources the authors used, how reliable these sources were, and how far removed in time the sources were from the stories they narrate, or if they were altered later. Scholars may also look into the internal evidence of the documents, to see if, for example, a document has misquoted texts from the Hebrew Tanakh, has made incorrect claims about geography, if the author appears to have hidden information, or if the author has fabricated a prophecy. Finally, scholars turn to external sources, including the testimony of early church leaders, to writers outside the church, primarily Jewish and Greco-Roman historians, who would have been more likely to have criticized the church, and to archaeological evidence.

Quest for the historical Jesus

[edit]

Conventionaly since the 18th century, three scholarly quests for the historical Jesus are distinguished, each with distinct characteristics and based on different research criteria, which were often developed during each specific phase.[19][104][20] These quests are distinguished from pre-Enlightenment approaches because they rely on the historical-critical method to study biblical narratives. While textual analysis of biblical sources had taken place for centuries, these quests introduced new methods and specific techniques in the attempt to establish the historical validity of their conclusions.[105]

According to Tucker Ferda, it is by now "conventional wisdom that the traditional threefold division of the quest for Jesus [...] is flawed".[106] The threefold terminology uses the literature selectively, poses an incorrect periodization of research, and fails to note that the quest did not begin with Reimarus, as Albert Schweitzer had claimed, but started earlier, with critical questions regarding the Christian origins narrative.[107][108][109][110]

First quest

[edit]The scholarly effort to reconstruct an "authentic" historical picture of Jesus was a product of the Enlightenment skepticism of the late eighteenth century.[111] Bible scholar Gerd Theissen explains that "It was concerned with presenting a historically true life of Jesus that functioned theologically as a critical force over against [established Roman Catholic] Christology."[111] The first scholar to separate the historical Jesus from the theological Jesus in this way was philosopher, writer, classicist, Hebraist and Enlightenment free thinker Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694–1768).[112] Copies of Reimarus' writings were discovered by G. E. Lessing (1729–1781) in the library at Wolfenbüttel where Lessing was the librarian. Reimarus had left permission for his work to be published after his death, and Lessing did so between 1774 and 1778, publishing them as Die Fragmente eines unbekannten Autors (The Fragments of an Unknown Author). Over time, they came to be known as the Wolfenbüttel Fragments after the library where Lessing worked. Reimarus distinguished between what Jesus taught and how he is portrayed in the New Testament. According to Reimarus, Jesus was a political messiah who failed at creating political change and was executed. His disciples then stole the body and invented the story of the resurrection for personal gain.[112][113]: 46–48 Reimarus' controversial work prompted a response from "the father of historical critical research" Johann Semler in 1779, Beantwortung der Fragmente eines Ungenannten (Answering the Fragments of an Unknown).[114] Semler refuted Reimarus' arguments, but it was of little consequence. Reimarus' writings had already made lasting changes by making it clear criticism could exist independently of theology and faith, and by founding historical Jesus studies within that non-sectarian view.[115][113]: 48

According to Homer W. Smith, the work of Lessing and others culminated in the Protestant theologian David Strauss's Das Leben Jesu ('The Life of Jesus', 1835), in which Strauss expresses his conclusion that Jesus existed, but that his godship is the result of "a historic nucleus [being] worked over and reshaped into an ideal form by the first Christians under the influence of Old Testament models and the idea of the messiah found in Daniel."[116]

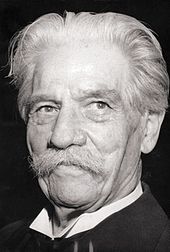

The enthusiasm shown during the first quest diminished after Albert Schweitzer's critique of 1906 in which he pointed out various shortcomings in the approaches used at the time. After Schweitzer's Von Reimarus zu Wrede was translated and published in English as The Quest of the Historical Jesus in 1910, the book's title provided the label for the field of study for eighty years.[117]: 779–

Second quest

[edit]The second quest began in 1953 and introduced a number of new techniques, but faded away in the 1970s.[118]

Third quest

[edit]In the 1980s a number of scholars gradually began to introduce new research ideas,[19][119] initiating a third quest characterized by the latest research approaches.[118][120] One of the modern aspects of the third quest has been the role of archaeology; James Charlesworth states that modern scholars now want to use archaeological discoveries that clarify the nature of life in Galilee and Judea during the time of Jesus.[121] A further characteristic of the third quest has been the interdisciplinary and global nature of its scholarship.[122] While the first two quests were mostly carried out by European Protestant theologians, a modern aspect of the third quest is the worldwide influx of scholars from multiple disciplines.[122] More recently, historicists have focused their attention on the historical writings associated with the era in which Jesus lived[123][124] or on the evidence concerning his family.[125][126][127][128]

By the end of the twentieth century, scholar Tom Holmén writes that Enlightenment skepticism had given way to a more "trustful attitude toward the historical reliability of the sources ... [Currently] the conviction of Sanders, (we know quite a lot about Jesus) characterizes the majority of contemporary studies."[129]: 43 Reflecting this shift, the phrase "quest for the historical Jesus" has largely been replaced by life of Jesus research.[130]: 33

Demise of authenticity and the "Next Quest"

[edit]Since the late 1900s, concerns have been growing about the usefulness of the criteria of authenticity.[131] According to Le Donne, the usage of such criteria is a form of "positivist historiography".[132] According to James DG Dunn, "What we actually have in the earliest retellings of what is now the Synoptic tradition...are the memories of the first disciples-not Jesus himself, but the remembered Jesus. The idea that we can get back to an objective historical reality, which we can wholly separate and disentangle from the disciples' memories...is simply unrealistic."[133] According to Chris Keith, a historical Jesus is "ultimately unattainable, but can be hypothesized on the basis of the interpretations of the early Christians, and as part of a larger process of accounting for how and why early Christians came to view Jesus in the ways that they did." According to Keith, "these two models are methodologically and epistemologically incompatible," calling into question the methods and aim of the first model.[134]

In 2021, James Crossley (editor of the Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus) announced that historical Jesus scholarship now had moved to the era of the Next Quest. The Next Quest has moved on from the criteria, obsessions with the uniqueness of Jesus, and the supersessionism still implicit in scholarly questions of the Jewishness of Jesus. Instead, sober scholarship now focuses on treating the subject matter as part of the wider human phenomenon of religion, cultural comparison, class relations, slave culture and economy, and the social history of historical Jesus scholarship and wider reception histories of the historical Jesus.[135] The book by Crossley and Robert J. Myles, Jesus: A Life in Class Conflict, is indicative of this new tendency.[136]

Others have criticized claims of a Fourth Quest and had a more measured response to critique of the criteria. The actual problem is arguably that critics use them inappropriately, trying to describe the history of minute portions of the Gospel text, rather than a true flaw in the historical logic of the criteria. According to Tucker Ferda, "...criticisms of the criteria have sometimes produced rather grandiose claims about their "uselessness," which do not seem justified when one looks at the kind of argument that those same critics will use when making positive claims about the historical Jesus...criticisms of the notion of "authenticity" or "historicity" can create the impression that there is more disagreement with earlier research than is actually the case."[137]

Methods

[edit]Textual, source and form-criticism

[edit]The first quest, which started in 1778, was almost entirely based on biblical criticism. This took the form of textual and source criticism originally, which were supplemented with form criticism in 1919, and redaction criticism in 1948.[105] Form criticism began as an attempt to trace the history of the biblical material during the oral period before it was written in its current form, and may be seen as starting where textual criticism ends.[138] Form criticism views Gospel writers as editors, not authors. Redaction criticism may be viewed as the child of source criticism and form criticism.[139] and views the Gospel writers as authors and early theologians and tries to understand how the redactor(s) has (have) molded the narrative to express their own perspectives.[139]

Criteria of authenticity

[edit]When form criticism questioned the historical reliability of the Gospels, scholars began looking for other criteria. Taken from other areas of study such as source criticism, the "criteria of authenticity" emerged gradually, becoming a distinct branch of methodology associated with life of Jesus research.[129]: 43–54 The criteria are a variety of rules used to determine if some event or person is more or less likely to be historical. These criteria are primarily, though not exclusively, used to assess the sayings and actions of Jesus.[140]: 193–199 [141]: 3–33

In view of the skepticism produced in the mid-twentieth century by form criticism concerning the historical reliability of the gospels, the burden shifted in historical Jesus studies from attempting to identify an authentic life of Jesus to attempting to prove authenticity. The criteria developed within this framework, therefore, are tools that provide arguments solely for authenticity, not inauthenticity.[129]: 43 In 1901, the application of criteria of authenticity began with dissimilarity. It was often applied unevenly with a preconceived goal.[111][129]: 40–45 In the early decades of the twentieth century, F. C. Burkitt and B. H. Streeter provided the foundation for multiple attestation. The Second Quest introduced the criterion of embarrassment.[105] By the 1950s, coherence was also included. By 1987, D. Polkow lists 25 separate criteria being used by scholars to test for historical authenticity including the criterion of "historical plausibility".[105][140]: 193–199

Criticism

[edit]A number of scholars have criticized the various approaches used in the study of the historical Jesus—on one hand, for the lack of rigor in research methods; on the other, for being driven by "specific agendas" that interpret ancient sources to fit specific goals.[142][143][144] By the 21st century, the "maximalist" approaches of the 19th century, which accepted all the gospels, and the "minimalist" trends of the early 20th century, which totally rejected them, were abandoned and scholars began to focus on what is historically probable and plausible about Jesus.[145][146][147]

Baptism and crucifixion

[edit]

There is widespread disagreement among scholars on the details of the life of Jesus mentioned in the gospel narratives, and on the meaning of his teachings.[15] Scholars differ on the historicity of specific episodes described in the biblical accounts of Jesus,[15][23] but almost all modern scholars consider his baptism and crucifixion to be historical facts.[12][148]

Baptism

[edit]The existence of John the Baptist within the same time frame as Jesus, and his eventual execution by Herod Antipas is attested to by 1st-century Roman-Jewish historian Josephus and the overwhelming majority of modern scholars view Josephus' accounts of the activities of John the Baptist as authentic.[149][150] One of the arguments in favor of the historicity of the Baptism of Jesus by John is the criterion of embarrassment, i.e. that it is a story which the early Christian Church would have never wanted to invent, as it implies that Jesus was subservient to John.[151][152][153] Another argument used in favour of the historicity of the baptism is that multiple accounts refer to it, usually called the criterion of multiple attestation.[154] Technically, multiple attestation does not guarantee authenticity, but only determines antiquity.[155] However, for most scholars, together with the criterion of embarrassment it lends credibility to the baptism of Jesus by John being a historical event.[154][156][157][158]

Crucifixion

[edit]John P. Meier views the crucifixion of Jesus as a historical fact and states that based on the criterion of embarrassment, Christians would not have invented the painful death of their leader.[159] Meier states that a number of other criteria – the criterion of multiple attestation (i.e., confirmation by more than one source), the criterion of coherence (i.e., that it fits with other historical elements) and the criterion of rejection (i.e., that it is not disputed by ancient sources) – help establish the crucifixion of Jesus as a historical event.[159] Eddy and Boyd state that it is now firmly established that there is non-Christian confirmation of the crucifixion of Jesus – referring to the mentions in Josephus and Tacitus.[88]

Most scholars in the third quest for the historical Jesus consider the crucifixion indisputable,[14][159][160][161] as do Bart Ehrman,[161] John Dominic Crossan[14] and James Dunn.[12] Although scholars agree on the historicity of the crucifixion, they differ on the reason and context for it, e.g. both E. P. Sanders and Paula Fredriksen support the historicity of the crucifixion, but contend that Jesus did not foretell his own crucifixion, and that his prediction of the crucifixion is a Christian story.[162] Géza Vermes also views the crucifixion as a historical event but believes this was due to Jesus’ challenging of Roman authority.[162] On the other hand, Maurice Casey and John P. Meier state that Jesus did predict his death, and this actually strengthened his followers' belief in his Resurrection.[163][164] Mara bar Serapion is the only source from the ancient world that mentions the execution of Jesus for the charge of "King of the Jews". Bart Ehrman states that Jesus portrayed himself as the leader of the future Kingdom and that a number of criteria – the criterion of multiple attestation and criterion of dissimilarity – establishes the crucifixion of Jesus as a enemy of state.[165]

Possibly historical elements

[edit]In addition to the two historical elements of baptism and crucifixion, scholars attribute varying levels of certainty to various other aspects of the life of Jesus, although there is no universal agreement among scholars on these items:[166][note 5]

- Jesus was a Galilean Jew who was born between 7 and 2 BC and died 30–36 AD.[170][171][172]

- Jesus lived only in Galilee and Judea:[173] Most scholars reject that there is any evidence that an adult Jesus traveled or studied outside Galilee and Judea. Marcus Borg states that the suggestions that an adult Jesus traveled to Egypt or India are "without historical foundation".[174] John Dominic Crossan states that none of the theories presented to fill the gap of 15–18 years between Jesus's early life and the start of his ministry have been supported by modern scholarship.[175][176] The Talmud refers to "Jesus the Nazarene" several times and scholars such as Andreas Kostenberger and Robert Van Voorst hold that some of these references are to Jesus.[177][176] Nazareth is not mentioned in the Hebrew Bible and the Christian gospels portray it as an insignificant village, John 1:46 asking "Can any good thing come out of Nazareth?"[178] Craig S. Keener states that it is rarely disputed that Jesus was from Nazareth, an obscure small village not worthy of invention.[178][179] Gerd Theissen concurs with that conclusion.[180]

- Jesus spoke Aramaic, and may have also spoken Hebrew and Greek.[181][182][183][184] The languages spoken in Galilee and Judea during the 1st century include the Semitic Aramaic and Hebrew languages as well as Greek, with Aramaic being the predominant language.[181][182]

- Jesus called disciples: John P. Meier sees the calling of disciples a natural consequence of the information available about Jesus.[166][13][185] N. T. Wright accepts that there were twelve disciples, but holds that the list of their names cannot be determined with certainty. John Dominic Crossan disagrees, stating that Jesus did not call disciples and had an "open to all" egalitarian approach, imposed no hierarchy and preached to all in equal terms.[13] However, James Crossley and Robert J. Myles and the emerging consensus disagree with Crossan, arguing that "we should dispel romantic notions that this movement was proudly egalitarian and progressive in the sense of the 'radical liberalism' of today" and instead point out that the core Twelve may have been "a central committee or politburo with membership sometimes changing."[186]

- Jesus caused a controversy at the Temple.[166][13][185]

- After his death his disciples continued, and some of his disciples were persecuted.[166][13]

- Jesus had a burial.[187][188][page needed]

Some scholars have proposed further additional historical possibilities such as:

- An approximate chronology of Jesus can be estimated from non-Christian sources, and confirmed by correlating them with New Testament accounts.[170][189]

- Claims about the appearance or ethnicity of Jesus are mostly subjective, based on cultural stereotypes and societal trends rather than on scientific analysis.[190][191][192]

- The baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist can be dated approximately from Josephus' references (Antiquities 18.5.2) to a date before AD 28–35.[149][193][194][195][196][excessive citations]

- The main topic of his teaching was the Kingdom of God, and he presented this teaching in parables that were surprising and sometimes confounding.[197]

- Jesus taught an ethic of forgiveness, as expressed in aphorisms such as "turn the other cheek" or "go the extra mile".[197] Within the traditional ethic of "Christian forgiveness" there are differing views regarding the nature of forgiveness as taught by Jesus.[198][better source needed]

- The date of the crucifixion of Jesus was earlier than 36 AD, based on the dates of the prefecture of Pontius Pilate who was governor of Roman Judea from 26 AD until 36 AD.[199][200][201]

Portraits of the historical Jesus

[edit]Scholars involved in the third and next quests for the historical Jesus have constructed a variety of portraits and profiles for Jesus.[24][25][202] However, there is little scholarly agreement on the portraits, or the methods used in constructing them.[23][28][29][203] The portraits of Jesus that have been constructed in the quest for the historical Jesus have often differed from each other, and from the image portrayed in the gospel accounts.[23] These portraits include that of Jesus as an apocalyptic prophet, charismatic healer, Cynic philosopher, Jewish Messiah and prophet of social change,[24][25] but there is little scholarly agreement on a single portrait, or the methods needed to construct it.[23][28][29] There are, however, overlapping attributes among the various portraits, and scholars who differ on some attributes may agree on others.[24][25][30] The conception of a "Historical Jesus" is limited to the abductions from modern scholars on the sources and the results can only produce fragments of what the "real Jesus" or "Jesus of history" may have been.[204] Such conceptions are merely a sketch or model which may inform about but never will be the real Jesus of history; similar to how models exist in the natural sciences that inform about phenomena without specifying a particular object.[205] W.R. Herzog has stated that: "What we call the historical Jesus is the composite of the recoverable bits and pieces of historical information and speculation about him that we assemble, construct, and reconstruct. For this reason, the historical Jesus is, in Meier's words, 'a modern abstraction and construct.'"[206]

Contemporary scholarship, representing the "third quest" and the "next quest" places Jesus firmly in the Jewish tradition. Jesus was a Jewish preacher who taught that he was the path to salvation, everlasting life, and the Kingdom of God.[22] A primary criterion used to discern historical details in the "third quest" is that of plausibility, relative to Jesus' Jewish context and to his influence on Christianity. Contemporary scholars of the "third quest" include E. P. Sanders, Géza Vermes, Gerd Theissen, Christoph Burchard, and John Dominic Crossan. In contrast to the Schweitzerian view, certain North American scholars, such as Burton Mack, advocate for a non-eschatological Jesus, one who is more of a Cynic sage than an apocalyptic preacher.[207]

Given that Jesus was poor, long-established historiographical approaches associated with the study of the poor in the past, such as microhistory, are relevant to the study of his life.[208]

Mainstream views

[edit]Despite the significant differences among scholars on what constitutes a suitable portrait for Jesus, the mainstream views supported by a number of scholars may be grouped together based on certain distinct, primary themes.[24][25] These portraits often include overlapping elements, and there are also differences among the followers of each portrait. The subsections below present the main portraits that are supported by multiple mainstream scholars.[24][25]

Apocalyptic prophet

[edit]

The apocalyptic prophet view primarily emphasizes Jesus preparing his fellow Jews for the End Times. The first proponent of this hypothesis was Albert Schweitzer in his 1906 book The Quest of the Historical Jesus.[209]

The works of E. P. Sanders and Maurice Casey place Jesus within the context of Jewish eschatological tradition.[210][211]: 169–204 [212]: 199–235 Bart D. Ehrman aligns himself with Schweitzer's view that Jesus expected an apocalypse during his own generation, and he bases some of his views on the argument that the earliest gospel sources (for which he assumes Markan priority) and the First Epistle to the Thessalonians, chapters 4 and 5, probably written by the end of AD 52, present Jesus as far more apocalyptic than other Christian sources produced towards the end of the 1st century, contending that the apocalyptic messages were progressively toned down.[213]

Dale C. Allison Jr. does not see Jesus as advocating specific timetables for the End Times, but sees him as preaching his own doctrine of "apocalyptic eschatology" derived from post-exilitic Jewish teachings,[214] and views the apocalyptic teachings of Jesus as a form of asceticism.[30] Other scholars follow most themes of the apocalyptic portrait, but take such teachings of Jesus as relating to the destruction of the Second Temple and not the end of the world[215][216][217][218][219][excessive citations] due to the wider significance of the Temple in Judaism that would warrant apocalyptic language.[220][221]

The characterization of Jesus as an apocalyptic or millenarian prophet can also be combined with other categories, such as in the work of James Crossley and Robert J. Myles (see below) who regard the end-time teaching of Jesus as a culturally credible way of responding to social and material upheaval in Galilee and Judea.[2]

Charismatic healer

[edit]

The charismatic healer portrait positions Jesus as a pious and holy man in the view of Géza Vermes, whose profile draws on the Talmudic representations of Jewish figures such as Hanina ben Dosa and Honi the Circle Drawer and presents Jesus as a Hasid.[222][223] Marcus Borg views Jesus as a charismatic "man of the spirit", a mystic or visionary who acts as a conduit for the "Spirit of God". Borg sees this as a well-defined religious personality type, whose actions often involve healing.[224] Borg sees Jesus as a non-eschatological figure who did not intend to start a new religion, but his message set him at odds with the Jewish powers of his time based on the "politics of holiness".[30] Both Sanders and Casey agree that Jesus was also a charismatic healer in addition to an apocalyptic prophet.[211]: 132–168 [212]: 237–279

Cynic philosopher

[edit]

In the Cynic philosopher profile, Jesus is presented as a Cynic, a traveling sage and philosopher preaching a cynical and radical message of change to abolish the existing hierarchical structure of the society of his time.[30][225] In John Dominic Crossan's view Jesus was crucified not for religious reasons but because his social teachings challenged the seat of power held by the Jewish authorities.[225] Crossan believes Galilee was a place where Greek and Jewish culture heavily interacted,[226] with Gadara, a day's walk from Nazareth, being a center of Cynic philosophy.[227][228] Burton Mack also holds that Jesus was a Cynic whose teachings were so different from those of his time that they shocked the audience and forced them to think, but Mack views his death as accidental and not due to his challenge to Jewish authority.[30]

Jewish Messiah

[edit]The Jewish Messiah portrait of N. T. Wright places Jesus within the Jewish context of "exile and return", a notion he uses to build on his view of the 1st-century concept of hope.[30] Wright believes that Jesus was the Messiah and argues that the Resurrection of Jesus was a physical and historical event.[225] Wright's portrait of Jesus is closer to the traditional Christian views than many other scholars, and when he departs from the Christian tradition, his views are still close to them.[225] Like Wright, Markus Bockmuehl, Peter Stuhlmacher and Brant J. Pitre support the view that Jesus came to announce the end of the Jewish spiritual exile and usher in a new messianic era in which God would improve this world through the faith of his people.[229][230]

Prophet of social change

[edit]The prophet of social change portrait positions Jesus primarily as someone who challenged the traditional social structures of his time.[231] Gerd Theissen sees three main elements to the activities of Jesus as he effected social change: his positioning as the Son of man, the core group of disciples that followed him, and his localized supporters as he journeyed through Galilee and Judea. Richard A. Horsley goes further and presents Jesus as a more radical reformer who initiated a grassroots movement.[232] David Kaylor's ideas are close to those of Horsley, but have a more religious focus and base the actions of Jesus on covenant theology and his desire for justice.[232] Elisabeth Fiorenza has presented a feminist perspective which sees Jesus as a social reformer whose actions such as the acceptance of women followers resulted in the liberation of some women of his time.[225][233] James Crossley and Robert J. Myles advocate a nuanced historical materialist perspective of Jesus as a religious organizer who responded to the intersecting material conditions of Galilee and Judea in culturally credible ways such as through intra-Jewish legal debate and a revolutionary millenarian proclamation.[2]

S. G. F. Brandon, Fernando Bermejo Rubio, and Reza Aslan argue that Jesus was an anti-Roman revolutionary that tried to overthrow Roman rule in Palestine and re-establish the Kingdom of Israel.[234][235][236]

Rabbi

[edit]The rabbi portrait advances the idea that Jesus was simply a rabbi who sought to reform certain ideas within Judaism. This idea can be traced to the late nineteenth century, when various liberal Jews sought to emphasize the Jewish nature of Jesus, and saw him as something of a proto-Reform Jew.[237] Perhaps the most prominent of these was Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch, who in The Doctrine of Jesus wrote:

We quote the rabbis of the Talmud; shall we then, not also quote the rabbi of Bethlehem? Shall not he in whom there burned, if it burned in anyone, the spirit and the light of Judaism, be reclaimed by the synagogue?[238]

Bruce Chilton, in his book Rabbi Jesus: An Intimate Biography, painted Jesus as a devout student of John the Baptist who came to see it as his mission to restore the Temple to purity, and purge the Romans and the corrupt priests from its midst.[239] Jaroslav Pelikan, in The Illustrated Jesus Through the Centuries stated:

Alongside Immanuel, "God with us" – the Hebrew title given to the child in the prophecy of Isaiah (7:14) and applied by Matthew (1:23) to Jesus, but not used to address him except in such apostrophes as the medieval antiphon Veni, Veni, Immanuel that forms the epigraph to this chapter – four Aramaic words appear as titles for Jesus: Rabbi, or teacher; Amen, or prophet; Messias, or Christ; and Mar, or Lord.

The most neutral and least controversial of these words is probably Rabbi, along with the related Rabbouni. Except for two passages, the Gospels apply the Aramaic word only to Jesus; and if we conclude that the title "teacher" or "master" (didaskalos in Greek) was intended as a translation of that Aramaic name, it seems safe to say that it was as Rabbi that Jesus was known and addressed.[26]

The conservative evangelical scholar Andreas J. Köstenberger in Jesus as Rabbi in the Fourth Gospel also reached the conclusion that Jesus was seen by his contemporaries as a rabbi.[27]

In 2012, the book Kosher Jesus by Orthodox Rabbi Shmuley Boteach was published in which Boteach takes the position that Jesus was a wise and learned Torah-observant Jewish rabbi. Boteach says he was a beloved member of the Jewish community. At the same time, Jesus is said to have despised the Romans for their cruelty, and to have fought them courageously. The book states that the Jews had nothing whatsoever to do with the murder of Jesus, but rather that the blame for his trial and killing lies with the Romans and Pontius Pilate. Boteach states clearly that he does not believe in Jesus as the Jewish Messiah. At the same time, Boteach argues that "Jews have much to learn from Jesus – and from Christianity as a whole – without accepting Jesus' divinity. There are many reasons for accepting Jesus as a man of great wisdom, beautiful ethical teachings, and profound Jewish patriotism."[240] He concludes by writing, as to Judeo-Christian values, that "the hyphen between Jewish and Christian values is Jesus himself."[241]

Non-mainstream views

[edit]Other portraits have been presented by individual scholars:

- Ben Witherington supports the "Wisdom Sage" view and states that Jesus is best understood as a teacher of wisdom who saw himself as the embodiment or incarnation of God's Wisdom.[225][233]

- John P. Meier's portrait of Jesus as the Marginal Jew is built on the view that Jesus knowingly marginalized himself in a number of ways, first by abandoning his profession as a carpenter and becoming a preacher with no means of support, then arguing against the teachings and traditions of the time while he had no formal rabbinic training.[30][225]

- Robert Eisenman proposed that James the Just was the Teacher of Righteousness mentioned in the Dead Sea Scrolls, and that the image of Jesus of the gospels was constructed by the Apostle Paul as pro-Roman propaganda.[242]

- Hyam Maccoby proposed that Jesus was a Pharisee, that the positions ascribed to the Pharisees in the Gospels are very different from what we know of them, and in fact their opinions were very similar to those ascribed to Jesus.[243] Harvey Falk also sees Jesus as proto-Pharisee or Essene.[244]

- Morton Smith views Jesus as a magician, a view based on the presentation of Jesus in later Jewish sources and on (dubious) apocryphal writings such as the Secret Gospel of Mark.[245]

- Leo Tolstoy saw Jesus as championing Christian anarchism (although Tolstoy never actually used the term "Christian anarchism"; reviews of his book following its publication in 1894 coined the term.)[246]

- It has been suggested by psychiatrists Oskar Panizza,[247][248][249] George de Loosten,[250] William Hirsch,[251] William Sargant,[252] Anthony Storr,[253][254][255] Raj Persaud,[256] psychologist Charles Binet-Sanglé[257] and others that Jesus had a mental disorder or psychiatric condition.[258] This theory is based on the fact that the Gospel of Mark (Mark 3:21) reports that When his family heard this they went out to restrain him, for they said, ″He is out of his mind.″[259] Psychologist Władysław Witwicki states that Jesus had difficulties communicating with the outside world and suffered from dissociative identity disorder (formerly known as multiple personality disorder), which made him a schizothymic or even schizophrenic type.[260][261] In 1998–2000 Polish author Leszek Nowak (born 1962) from Poznań authored a study in which, based on his own history of delusions of mission and overvalued ideas, and information communicated in the Gospels, made an attempt at reconstructing Jesus’ psyche[262] with the view of the apocalyptic prophet.[263]

See also

[edit]- Biblical archaeology

- Biblical manuscript

- Census of Quirinius, a census of Judaea which was taken by Publius Sulpicius Quirinius, Roman governor of Syria, upon the imposition of direct Roman rule in AD 6.

- Christ myth theory

- Criterion of dissimilarity

- Criticism of the Bible

- Chronology of Jesus

- Gospel harmony

- Historical background of the New Testament

- Historicity of the Bible

- Jesus in comparative mythology

- Jesus Seminar

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Mental health of Jesus

- New Testament places associated with Jesus

- Race and appearance of Jesus

- Sexuality of Jesus

- Scholarly interpretation of Gospel elements

- Son of God

- Timeline of Christianity

- The World's Sixteen Crucified Saviors

Notes

[edit]- ^ In Galatians 4:4, Paul states that Jesus was "born of a woman."

- ^ In Romans 1:3, Paul states that Jesus was "born under the law."

- ^ That Jesus had a brother named James is corroborated by Josephus.[61]

- ^ Ehrman says, "There is historical information about Jesus in the Gospels."[42]: 14

- ^ Additional elements:

- Bible scholars James Beilby and Paul Eddy write that consensus is "elusive but not entirely absent".[167] According to Beilby and Eddy, "Jesus was a first-century Jew, who was baptized by John, went about teaching and preaching, had followers, was believed to be a miracle worker and exorcist, went to Jerusalem where there was an "incident", was subsequently arrested, convicted and crucified."[168]

- Amy-Jill Levine has stated that "there is a consensus of sorts on the basic outline of Jesus' life. Most scholars agree that Jesus was baptized by John, debated with fellow Jews on how best to live according to God’s will, engaged in healings and exorcisms, taught in parables, gathered male and female followers in Galilee, went to Jerusalem, and was crucified by Roman soldiers during the governorship of Pontius Pilate (26–36 CE)."[169]

References

[edit]- ^ Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. pp. 779–. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- ^ a b c Crossley, James and Robert J. Myles (2023). Jesus: A Life in Class Conflict. Zer0 Books. ISBN 978-1-80341-082-1.

- ^ a b Amy-Jill Levine in The Historical Jesus in Context edited by Amy-Jill Levine et al. 2006 Princeton Univ Press ISBN 978-0-691-00992-6 pp. 1–2

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (1999), Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium ISBN 0195124731 Oxford University Press pp. ix–xi

- ^ Ehrman, Bart (2003). The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515462-2, chapters 13, 15

- ^ a b Webb, Robert; Bock, Darrell, eds. (13 March 2024). Key Events in the Life of the Historical Jesus: A Collaborative Exploration of Context and Coherence. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. pp. 1–3. ISBN 9783161501449.

- ^ Law, Stephen (2011). "Evidence, Miracles, and the Existence of Jesus". Faith and Philosophy. 28 (2): 129. doi:10.5840/faithphil20112821.

- ^ a b c d e In a 2011 review of the state of modern scholarship, Bart Ehrman (a secular agnostic) wrote: "He certainly existed, as virtually every competent scholar of antiquity, Christian or non-Christian, agrees, based on certain and clear evidence." B. Ehrman, 2011 Forged: writing in the name of God ISBN 978-0-06-207863-6. pp. 256–257

- ^ a b Robert M. Price (an atheist who denies the existence of Jesus) agrees that this perspective runs against the views of the majority of scholars: Robert M. Price "Jesus at the Vanishing Point" in The Historical Jesus: Five Views edited by James K. Beilby & Paul Rhodes Eddy, 2009 InterVarsity, ISBN 028106329X p. 61

- ^ a b c Michael Grant (a classicist) states that "In recent years, 'no serious scholar has ventured to postulate the non-historicity of Jesus' or at any rate very few, and they have not succeeded in disposing of the much stronger, indeed very abundant, evidence to the contrary." in Jesus: An Historian's Review of the Gospels by Michael Grant (2004) ISBN 1898799881 p. 200

- ^ Burridge & Gould 2004, p. 34. "There are those who argue that Jesus is a figment of the Church’s imagination, that there never was a Jesus at all. I have to say that I do not know any respectable critical scholar who says that anymore."

- ^ a b c Jesus Remembered by James D. G. Dunn 2003 ISBN 0-8028-3931-2 p. 339 states of baptism and crucifixion that these "two facts in the life of Jesus command almost universal assent".

- ^ a b c d e Prophet and Teacher: An Introduction to the Historical Jesus by William R. Herzog (2005) ISBN 0664225284 pp. 1–6

- ^ a b c Crossan, John Dominic (1995). Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography. HarperOne. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-06-061662-5.

That he was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be, since both Josephus and Tacitus ... agree with the Christian accounts on at least that basic fact.

- ^ a b c Powell, Mark Allan (1998). Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 168–173. ISBN 978-0-664-25703-3.

- ^ a b Van Voorst, Robert E. (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence ISBN 0-8028-4368-9.

- ^ a b Bockmuehl, Markus N. A. (2001). The Cambridge Companion to Jesus. Cambridge University Press. pp. 121–125. ISBN 978-0521796781.

- ^ a b Chilton, Bruce; Evans, Craig A. (1998). Studying the Historical Jesus: Evaluations of the State of Current Research. BRILL. pp. 460–470. ISBN 978-9004111424.

- ^ a b c Witherington III 1997, pp. 9–13.

- ^ a b Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee by Mark Allan Powell, Westminster John Knox Press (1999) ISBN 0664257038 pp. 19–23

- ^ a b c Sanders, E. P. The historical figure of Jesus. Penguin, 1993.

- ^ a b Theissen & Merz 1998.

- ^ a b c d e f Theissen & Winter 2002, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 pp. 124–125

- ^ a b c d e f g Mitchell, Margaret M.; Young, Frances M., eds. (2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-521-81239-9.

- ^ a b Pelikan, Jaroslav. "Jesus as Rabbi". PBS. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

four Aramaic words appear as titles for Jesus: Rabbi, or teacher; Amen, or prophet; Messias, or Christ; and Mar, or Lord

- ^ a b Köstenberger, Andreas (1998). "Jesus as Rabbi in the Fourth Gospel". Bulletin for Biblical Research. 8: 97–128. doi:10.5325/bullbiblrese.8.1.0097. JSTOR 26422158. S2CID 203287514.

- ^ a b c Charlesworth, James H.; Pokorny, Petr, eds. (2009). Jesus Research: An International Perspective (Princeton–Prague Symposia Series on the Historical Jesus). Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-8028-6353-9.

- ^ a b c Porter, Stanley E.; Hayes, Michael A.; Tombs, David (2004). Images of Christ (Academic Paperback). T&T Clark. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-567-04460-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h McClymond, Michael James (2004). Familiar Stranger: An Introduction to Jesus of Nazareth. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 16–22. ISBN 978-0-8028-2680-0.

- ^ Jesus Now and Then by Richard A. Burridge and Graham Gould (2004) ISBN 0802809774 p. 34

- ^ Grant, Michael (1992) [1977]. Jesus: An Historian's Review of the Gospels (1st Collier Books ed.). New York: Collier Books. p. 208. ISBN 0020852517. OCLC 25833417.

- ^ Encyclopedia of theology: a concise Sacramentum mundi by Karl Rahner 2004 ISBN 0860120066 pp. 730–731

- ^ Van Voorst, Robert E (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0802843689 p. 15

- ^ James F. McGrath, James F. McGrath. "Fringe view: The world of Jesus mythicism..." The Christian Century. Christian Century. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Eddy, Paul Rhodes; Boyd, Gregory A. (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0801031144.

- ^ Sykes, Stephen W. (2007). "Paul's understanding of the death of Jesus". Sacrifice and Redemption. Cambridge University Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0521044608.

- ^ Theissen, Gerd; Merz, Annette (1996). The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0800631222.

- ^ a b Did Jesus exist?, Bart Ehrman, 2012, Chapter 1

- ^ Van Voorst 2000, p. 16

- ^ The Gospels and Jesus by Graham Stanton, 1989 ISBN 0192132415 Oxford University Press, p. 145:

- ^ a b c d Ehrman, Bart (2012). Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0062206442.

- ^ Bart Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist? Harper Collins, 2012, p. 12, "Earl Doherty defines the view...In simpler terms, the historical Jesus did not exist. Or if he did, he had virtually nothing to do with the founding of Christianity." Further quoting as representative the fuller definition provided by Doherty in Jesus: Neither God Nor Man. Age of Reason, 2009, pp. vii–viii: it is "the theory that no historical Jesus worthy of the name existed, that Christianity began with a belief in a spiritual, mythical figure, that the gospels are essentially allegory and fiction, and that no single identifiable person lay at the root of the Galilean preaching tradition."

- ^ Richard Dawkins (2007). The God Delusion. Lulu.com. p. 122. ISBN 978-1430312307.

- ^ God is Not Great, Christopher Hitchens, 2007, Chapter 8

- ^ "The Messiah Myth: The Near Eastern Roots of Jesus and David" Thomas L. Thompson Basic Book Perseus Books' 2005

- ^ "Jesus Outside the New Testament" Robert E. Van Voorst, 2000, pp. 8–9

- ^ Price, Robert M. (2009). "Jesus at the Vanishing Point". In Beilby, James K.; Eddy, Paul R. (eds.). The Historical Jesus: Five Views. InterVarsity Press. pp. 55–83. ISBN 978-0-8308-3868-4

- ^ a b Burridge & Gould 2004, p. 34.

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0802843689 p.16 states: "biblical scholars and classical historians regard theories of non-existence of Jesus as effectively refuted"

- ^ James D. G. Dunn "Paul's understanding of the death of Jesus" in Sacrifice and Redemption edited by S. W. Sykes (2007) Cambridge University Press ISBN 052104460X pp. 35–36 states that the theories of the non-existence of Jesus are "a thoroughly dead thesis"

- ^ Robert M. Price "Jesus at the Vanishing Point" in The Historical Jesus: Five Views edited by James K. Beilby & Paul Rhodes Eddy, 2009 InterVarsity, ISBN 028106329X p. 61

- ^ Theissen, Gerd; Merz, Annette (1996). The Historical Jesus. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press. pp. 17–62. ISBN 978-0-8006-3122-2.

- ^ Edward Adams in The Cambridge Companion to Jesus by Markus N. A. Bockmuehl 2001 ISBN 0521796784 pp. 94–96.

- ^ Eddy, Paul Rhodes; Boyd, Gregory A. (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. Baker Academic. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-8010-3114-4.

- ^ Tuckett, Christopher M. (2001). Markus N. A. Bockmuehl (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Jesus. Cambridge University Press. pp. 122–126. ISBN 978-0521796781.

- ^ Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making by James D. G. Dunn (2003) ISBN 0802839312 p. 143

- ^ Jesus Christ in History and Scripture by Edgar V. McKnight 1999 ISBN 0865546770 p. 38

- ^ Jesus according to Paul by Victor Paul Furnish 1994 ISBN 0521458242 pp. 19–20

- ^ Galatians 1:19

- ^ Murphy, Caherine M. (2007). The Historical Jesus For Dummies. For Dummies. p. 140. ISBN 978-0470167854.

- ^ Ehrman 2012, pp. 144–146.

- ^ Evans, Craig (2016). "Mythicism and the Public Jesus of History". Christian Research Journal. 39 (5).

- ^ Longenecker, Bruce, ed. (2020). The New Cambridge Companion to St. Paul. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1108438285.

- ^ Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey by Craig L. Blomberg 2009 ISBN 0805444823 pp. 441–442

- ^ "Jesus Christ". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

The Synoptic Gospels, then, are the primary sources for knowledge of the historical Jesus

- ^ Vermes, Geza. The authentic gospel of Jesus. London, Penguin Books. 2004.

- ^ "Luke, Chapter 8 | USCCB". bible.usccb.org.

- ^ "Matthew, Chapter 14 | USCCB". bible.usccb.org.

- ^ Mark Allan Powell (editor), The New Testament Today, p. 50 (Westminster John Knox Press, 1999). ISBN 0-664-25824-7

- ^ Stanley E. Porter (editor), Handbook to Exegesis of the New Testament, p. 68 (Leiden, 1997). ISBN 90-04-09921-2

- ^ Crossley & Myles 2023, p. 15

- ^ "Historical Criticism". The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Routledge. 2008. p. 283. ISBN 9780415880886.

- ^ Davies, W. D.; Sanders, E.P. (2008). "20. Jesus: From the Jewish Point of View". In Horbury, William; Davies, W.D.; Sturdy, John (eds.). The Cambridge History of Judaism. Volume 3: The Early Roman period. Cambridge Univiversity Press. p. 620. ISBN 9780521243773.

- ^ Theissen, Gerd; Merz, Annette. The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-0863-8.

- ^ Green, Joel B. (2013). Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels (2nd ed.). IVP Academic. p. 541. ISBN 978-0830824564.

- ^ a b Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey by Craig L. Blomberg 2009 ISBN 0-8054-4482-3 pp. 431–436

- ^ Bruce, Frederick Fyvie (1974). Jesus and Christian Origins Outside the New Testament. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-80281-575-0.

- ^ a b c Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000. pp. 39–53

- ^ Schreckenberg, Heinz; Kurt Schubert (1992). Jewish Traditions in Early Christian Literature. ISBN 978-90-232-2653-6.

- ^ Kostenberger, Andreas J.; L. Scott Kellum; Charles L. Quarles (2009). The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament. B&H Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3.

- ^ The new complete works of Josephus by Flavius Josephus, William Whiston, Paul L. Maier ISBN 0-8254-2924-2 pp. 662–663

- ^ Josephus XX by Louis H. Feldman 1965, ISBN 0674995023 p. 496

- ^ Van Voorst, Robert E. (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence ISBN 0-8028-4368-9. p. 83

- ^ Flavius Josephus; Maier, Paul L. (December 1995). Josephus, the essential works: a condensation of Jewish antiquities and The Jewish war ISBN 978-0-8254-3260-6 pp. 284–285

- ^ P. E. Easterling, E. J. Kenney (general editors), The Cambridge History of Latin Literature, p. 892 (Cambridge University Press, 1982, reprinted 1996). ISBN 0-521-21043-7

- ^ Tuckett, Christopher (2001). "8. Sources and Methods". The Cambridge Companion to Jesus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0521796781.

Tacitus' reference to Jesus is extremely brief, but it shows no evidence of later Christian influence and hence is widely accepted as genuine. It does then provide independent, non-Christian evidence at least for Jesus' existence and his execution under Pilate.

- ^ a b Eddy; Boyd (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. Baker Academic. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-8010-3114-4.

- ^ Maier, Johann (1978). Jesus von Nazareth in der talmudischen Überlieferung (in German). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, [Abt. Verlag]. ISBN 978-3-534-04901-1.

- ^ Davidson, William. "Sanhedrin 43a". sefaria.org. Sefaria. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Theissen & Merz 1998, p. 76.

- ^ Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence by Robert E. Van Voorst 2000 ISBN 0-8028-4368-9 pp. 53–55

- ^ Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies by Craig A. Evans 2001 ISBN 978-0-391-04118-9 p. 41

- ^ Soulen, Richard N.; Soulen, R. Kendall (2001). Handbook of biblical criticism (3rd., rev. and expanded ed.). Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-664-22314-4.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D.; Evans, Craig A.; Stewart, Robert B. (2020). Can we trust the Bible on the Historical Jesus?. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 12–18. ISBN 9780664265854.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D.; Evans, Craig A.; Stewart, Robert B. (2020). Can we trust the Bible on the Historical Jesus?. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664265854.

- ^ Craig Evans, "Life-of-Jesus Research and the Eclipse of Mythology," Theological Studies 54 (1993) p. 13-14 "First, the New Testament Gospels are now viewed as useful, if not essentially reliable, historical sources. Gone is the extreme skepticism that for so many years dominated gospel research. Representative of many is the position of E. P. Sanders and Marcus Borg, who have concluded that it is possible to recover a fairly reliable picture of the historical Jesus."

- ^ “The Historical Figure of Jesus," Sanders, E.P., Penguin Books: London, 1995, p. 3.

- ^ Fire of Mercy, Heart of the Word (Vol. II): Meditations on the Gospel According to St. Matthew – Dr Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis, Ignatius Press, Introduction

- ^ Grant, Robert M. "A Historical Introduction to the New Testament (Harper and Row, 1963)". Religion-Online.org. Archived from the original on 21 June 2010.

- ^ Blomberg, Craig L. (2007). The Historical Reliability of the Gospels (2. ed.). IVP Academic. ISBN 9780830828074.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. Harper San Francisco. pp. 89–90.

- ^ Paul Rhodes Eddy & Gregory A. Boyd, The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. (2008, Baker Academic). 309-262.[page needed]

- ^ Theissen & Winter 2002, pp. 1–6.

- ^ a b c d Criteria for Authenticity in Historical–Jesus Research by Stanley E. Porter 2004 ISBN 0567043606 pp. 100–120

- ^ Ferda, Tucker (2024). Jesus and His Promised Second Coming: Jewish Eschatology and Christian Origins. Eerdmans. p. 29. ISBN 9780802879905.

- ^ Ferda, Tucker (2024). Jesus and His Promised Second Coming: Jewish Eschatology and Christian Origins. Eerdmans. p. 29-30. ISBN 9780802879905.

- ^ Baird, William (1992). From Deism to Tubingen, vol. 1 of History of New Testament Research. Fortress Press. p. 3-57. ISBN 978-0800626266.

- ^ Paget, James (2001). "Quests for the Historical Jesus" in The Cambridge Companion to Jesus. Cambridge University Press. p. 140-141. ISBN 978-0521796781.

- ^ Birch, Jonathan (2011). "The Road to Reimarus: Origins of the Quest of the Historical Jesus" in Holy Land as Homeland?. Sheffield Phoenix Press. p. 19-47. ISBN 978-1907534324.

- ^ a b c Theissen & Winter 2002, p. 1.

- ^ a b Groetsch, Ulrich (2015). Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694–1768): Classicist, Hebraist, Enlightenment Radical in Disguise. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-27299-6.

- ^ a b Law, David R. (2012). "A Brief history of Historical criticism: the nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century". The Historical-Critical Method: A Guide for the Perplexed. New York: T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-56740-012-3.

- ^ Rollman, H. (1998). "Johann Salomo Semler". In McKim, Donald K. (ed.). Handbook of Major Bible Interpreters. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. pp. 43–45, 355–359. ISBN 978-0-83081-452-7.

- ^ Brown, Colin (1998). "Reimarus, Hermann Samuel". In McKim, Donald K. (ed.). Historical Handbook of Major Biblical Interpreters. Downer's Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. pp. 346–350. ISBN 978-0-8308-1452-7.

- ^ Smith, Homer W. (1952). Man and His Gods. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. p. 385.

- ^ Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- ^ a b Robert E. Van Voorst Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0-8028-4368-9 pp. 2–6

- ^ The Symbolic Jesus: Historical Scholarship, Judaism and the Construction of Contemporary Identity by William Arnal, Routledge 2005 ISBN 1845530071 pp. 41–43

- ^ Criteria for Authenticity in Historical-Jesus Research by Stanley E. Porter, Bloomsbury 2004 ISBN 0567043606 pp. 28–29

- ^ "Jesus Research and Archaeology: A New Perspective" by James H. Charlesworth in Jesus and archaeology edited by James H. Charlesworth 2006 ISBN 0-8028-4880-X pp. 11–15

- ^ a b Soundings in the Religion of Jesus: Perspectives and Methods in Jewish and Christian Scholarship by Bruce Chilton, Anthony Le Donne, and Jacob Neusner (2012) ISBN 0800698010 p. 132

- ^ Mason, Steve (2002), "Josephus and the New Testament" (Baker Academic)

- ^ Tabor, James (2012)"Paul and Jesus: How the Apostle Transformed Christianity" (Simon & Schuster)

- ^ Eisenman, Robert (1998), "James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls" (Watkins)

- ^ Butz, Jeffrey "The Brother of Jesus and the Lost Teachings of Christianity" (Inner Traditions)

- ^ Tabor, James (2007), "The Jesus Dynasty: The Hidden History of Jesus, His Royal Family, and the Birth of Christianity"

- ^ Price, Robert M. (14 September 2007). "The New Testament Code: The Cup of the Lord, The Damascus Covenant, and the Blood of Christ – By Robert Eisenman". Religious Studies Review. 33 (2): 153. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0922.2007.00176_38.x. ISSN 0319-485X.

- ^ a b c d Holmén, Tom (2008). Evans, Craig A. (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-97569-8.

- ^ Telford, William R. (1998). "Major trends and interpretive issues in the study of Jesus". In Chilton, Bruce David; Evans, Craig Alan (eds.). Studying the Historical Jesus: Evaluations of the State of Current Research. Boston, Massachusetts: Brill. ISBN 90-04-11142-5.

- ^ Keith, Chris; Le Donne, Anthony, eds. (2012), Jesus, Criteria, and the Demise of Authenticity, Bloomsbury Publishing

- ^ Thinkapologtics.com, Book Review: Jesus, Criteria, and the Demise of Authenticity, by Chris Keith and Anthony Le Donne Archived 2019-04-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dunn, James D.G (2003). Christianity in the making Volume 1. Jesus Remembered. William B. Eerdmans. p. 130-131.

- ^ Chris Keith (2016), The Narratives of the Gospels and the Historical Jesus: Current Debates, Prior Debates and the Goal of Historical Jesus Research Archived 2021-08-24 at the Wayback Machine, Journal for the Study of the New Testament.

- ^ James Crossley (2021), [https://web.archive.org/web/20220607111843/https://brill.com/view/journals/jshj/19/3/article-p261_261.xml Archived 2022-06-07 at the Wayback Machine The Next Quest for the Historical Jesus, Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus.

- ^ Crossley & Myles 2023

- ^ Ferda, Tucker (2018). Jesus, the Gospels, and the Galilean Crisis: The Origins, Reception, and Value of an Influential Hypothesis. T&T Clark. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0567679932.

- ^ The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology by Alan Richardson 1983 ISBN 0664227481 pp. 215–216

- ^ a b Interpreting the New Testament by Daniel J. Harrington (1990) ISBN 0814651240 pp. 96–98

- ^ a b Denton, Donald L. Jr. (2004). "Appendix 1". Historiography and Hermeneutics in Jesus Studies: An Examination of the Work of John Dominic Crossan and Ben F. Meyer. New York: T&T Clark Int. ISBN 978-0-56708-203-9.

- ^ Hägerland, Tobias, ed. (2016). "Problems of Method for studying Jesus and the scriptures". Jesus and the Scriptures: Problems, Passages and Patterns. New York: Bloomsbury T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-56766-502-7.

- ^ Allison, Dale (2009). The Historical Christ and the Theological Jesus. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-8028-6262-4. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

We wield our criteria to get what we want.

- ^ John P. Meier (2009). A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Law and Love. Yale University Press. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-0-300-14096-5. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Clive Marsh, "Diverse Agendas at Work in the Jesus Quest" in Handbook for the Study of the Historical Jesus by Tom Holmen and Stanley E. Porter (2011) ISBN 9004163727 pp. 986–1002

- ^ John P. Meier "Criteria: How do we decide what comes from Jesus?" in The Historical Jesus in Recent Research by James D. G. Dunn and Scot McKnight (2006) ISBN 1575061007 p. 124 "Since in the quest for the historical Jesus almost anything is possible, the function of the criteria is to pass from the merely possible to the really probable, to inspect various probabilities, and to decide which candidate is most probable. Ordinarily, the criteria can not hope to do more."

- ^ The Historical Jesus of the Gospels by Craig S. Keener (2012) ISBN 0802868886 p. 163

- ^ Jesus in Contemporary Scholarship by Marcus J. Borg (1994) ISBN 1563380943 pp. 4–6

- ^ Jesus of Nazareth by Paul Verhoeven (2010) ISBN 1583229051 p. 39

- ^ a b Craig Evans, 2006 "Josephus on John the Baptist" in The Historical Jesus in Context edited by Amy-Jill Levine et al. Princeton Univ Press ISBN 978-0-691-00992-6 pp. 55–58

- ^ The new complete works of Josephus by Flavius Josephus, William Whiston, Paul L. Maier ISBN 0-8254-2924-2 pp. 662–663

- ^ Jesus as a figure in history: how modern historians view the man from Galilee by Mark Allan Powell 1998 ISBN 0-664-25703-8 p. 47

- ^ Who Is Jesus? by John Dominic Crossan, Richard G. Watts 1999 ISBN 0664258425 pp. 31–32

- ^ Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching by Maurice Casey 2010 ISBN 0-567-64517-7 p. 35

- ^ a b John the Baptist: prophet of purity for a new age by Catherine M. Murphy 2003 ISBN 0-8146-5933-0 pp. 29–30

- ^ Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies by Craig A. Evans 2001 ISBN 0-391-04118-5 p. 15

- ^ An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity by Delbert Royce Burkett 2002 ISBN 0-521-00720-8 pp. 247–248

- ^ Who is Jesus? by Thomas P. Rausch 2003 ISBN 978-0-8146-5078-3 p. 36

- ^ The relationship between John the Baptist and Jesus of Nazareth: A Critical Study by Daniel S. Dapaah 2005 ISBN 0-7618-3109-6 p. 91

- ^ a b c John P. Meier "How do we decide what comes from Jesus" in The Historical Jesus in Recent Research by James D. G. Dunn and Scot McKnight 2006 ISBN 1-57506-100-7 pp. 126–128, 132–136

- ^ Blomberg, Craig L. (2009). Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey. ISBN 0-8054-4482-3 pp. 211–214

- ^ a b Ehrman, Bart D. (2008). A Brief Introduction to the New Testament. ISBN 0-19-536934-3 p. 136

- ^ a b A Century of Theological and Religious Studies in Britain, 1902–2002 by Ernest Nicholson 2004 ISBN 0-19-726305-4 pp. 125–126

- ^ Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching. A&C Black. p. 507. ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3.

- ^ Meier, John P. (1991). A Marginal Jew: The roots of the problem and the person. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-26425-9.

- ^ Erhman, Bart (1999). Jesus:the apocalyptic prophet of the new millenium. Oxford University Press. p. 222. ISBN 9780195124743.

- ^ a b c d Chilton, Bruce D.; Evans, Craig A. (2002). Authenticating the Activities of Jesus. Boston: Brill. pp. 3–7. ISBN 0-391-04164-9.

- ^ Beilby & Eddy 2009, p. 47.

- ^ Beilby & Eddy 2009, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Levine, Amy-Jill (2006). The Historical Jesus in Context. Princeton University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-691-00992-6.

- ^ a b Vardaman, Jerry; Yamauchi, Edwin M. (1989). Chronos, Kairos, Christos. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. pp. 113–129. ISBN 0-931464-50-1.

- ^ Köstenberger, Andreas J.; Kellum, Leonard Scott; Quarles, Charles Leland (2009). The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament. B&H. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3.

- ^ Geoffrey Blainey; A Short History of Christianity; Viking; 2011; p. 3

- ^ Green, Joel B.; McKnight, Scot; Marshall, I. Howard (1992), Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels. InterVarsity Press. p. 442

- ^ Dunn, James D. G.; McKnight, Scot, eds. (2005). The Historical Jesus in Recent Research. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. p. 303. ISBN 1-57506-100-7.

- ^ Crossan, John Dominic; Watts, Richard G. (1999). Who is Jesus?. Westminster John Knox. pp. 28–29. ISBN 0-664-25842-5.

- ^ a b Voorst, Robert Van (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 117–118. ISBN 0-8028-4368-9.

- ^ Kostenberger, Kellum & Quarles 2009, pp. 107–109.

- ^ a b The Life and Ministry of Jesus by Douglas Redford 2007 ISBN 0-7847-1900-4 p. 32

- ^ Keener, Craig S. (2012). The Historical Jesus of the Gospels. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6888-6. 182

- ^ Theissen & Merz 1998, p. 165, "Our conclusion must be that Jesus came from Nazareth.".

- ^ a b James Barr, Which language did Jesus speak, Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester, 1970; 53(1) pp. 9–29 [1] Archived 2018-12-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Porter, Stanley E. (1997). Handbook to exegesis of the New Testament. Leiden: Brill. pp. 110–112. ISBN 90-04-09921-2.

- ^ Hoffmann, R. Joseph; Larue, Gerald A. (1986). Jesus in History and Myth. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus. p. 98. ISBN 0-87975-332-3.